As King Arthur: Legend of the Sword hits our screens, find out the surprising part the mythical king played in the conquest of Wales.

The roles played by the figure of King Arthur in history, legend and myth are many and varied, and they continue to evolve through movies, literature and more.

One of the more surprising places to find the character involved, though, was lending a helping hand to the English King Edward I’s conquest of Wales in the thirteenth century.

If Arthur existed at all he was, of course, a Brythonic (British) leader from the post-Roman period, involved in the military resistance of the native British against the invading Anglo-Saxons – the forefathers of the later kings of England.

The Kings of the Britons

In the centuries after Arthur’s supposed existence, Brythonic political power went into serious decline and the independence of Brythonic leaders in the island was eventually restricted to the lands that would become Wales.

Within Wales itself there were a variety of competing kings and kingdoms, but the most powerful leaders sought to use the legend of Arthur to raise themselves above their peers.

These leaders were labelled in the Welsh chronicles as ‘Kings of the Britons’ and the greatest of them – Gruffudd ap Llywelyn (d. 1063) – was the only native ruler to be king of all Wales.

The title ‘King of the Britons’ implies a connection to the Arthurian history and mythology that saw the Britons as the descendants of the survivors of Troy.

These Trojans had conquered the whole island of Britain from the giants, meaning their descendants were the rightful kings and superior to any Anglo-Saxon (‘English’) overlord.

Geoffrey of Monmouth

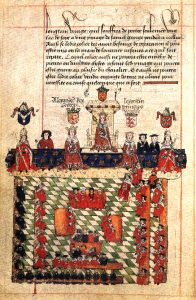

In the early twelfth century, Geoffrey of Monmouth – a Welsh cleric in the service of the Anglo-Normans – wrote his History of the Kings of Britain, a work of pseudo-history that expanded this mythology and brought it to the attention of the wider European world.

The tales proved incredibly popular and influential across the continent, as revealed by the hundreds of medieval manuscript copies that survive.

Enthusiasm for Geoffrey’s work was as keen in England as elsewhere, but this audience had a unique problem to deal with.

Although Geoffrey had no truck with the claims of contemporary Welsh kings to superiority (or even equality) with English kings, the historical supremacy of British (‘Welsh’) kings over the whole island sat uncomfortably with an audience east of the river Severn.

The princes of Wales

By the thirteenth century, the partial conquest of Wales and the related in-fighting between the surviving native dynasties meant that the ambitions of its rulers had contracted.

The emerging princes of Wales – the rulers of Gwynedd – still tapped into Arthurian mythology as they sought supremacy over the other Welsh leaders, but inherent in their theory of rule was the ultimate overlordship of the king of England.

The nature and extent of this overlordship would be disputed, but the princes accepted the story – first recorded by Geoffrey of Monmouth – of the division of Britain between the sons of Brutus the Trojan; Locrinus, Albanactus and Camber.

Locrinus – the eldest, who ruled ‘England’ – was acknowledged as the superior king over the other two, who ruled ‘Scotland’ and ‘Wales’.

The Scots would reject this tale that gave England supremacy, denying any Trojan heritage and promoting their own mythology that based their claims to the Scottish crown on Scota, the daughter of an Egyptian Pharaoh from the time of Moses.

In Wales, the greatest English acknowledgement of the rights of the native principality came in the 1267 Treaty of Montgomery.

Under its terms, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd secured the homage and fealty of almost all the native Welsh nobility. But, in his moment of triumph, the prince formally accepted the position of tenant-in-chief of the king of England and that his position had been granted to him by that king, something that also carried the seal of papal approval.

King Edward I and the story of Arthur

Edward had been alongside his father, King Henry III, when the Treaty of Montgomery was sealed.

The heir to the throne was well versed in Arthurian mythology, as was his wife, Eleanor of Castile, thanks to the dispersal of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s work throughout the courts of Europe.

Relations between Edward and Llywelyn were good at the time, but the accord was destroyed in the 1270s in disputes that centred around the nature of the new king’s overlordship, and in 1277 an English campaign forced the prince’s near-total submission.

It was in the aftermath of the 1277 war that the importance of the Arthurian legend to both English and Welsh becomes clear.

In early 1278 the king and his court were at the Iron Age hillfort of South Cadbury (Somerset), an imposing site that was already associated with Arthur’s Camelot.

The royal party had moved on to Glastonbury in time for Easter, seemingly in order to fulfil the personal interests Edward and his wife had in the Arthurian legend, but also to reinforce the king’s favoured interpretation of it.

The Welsh believed that Arthur had not died, that he was wounded and taken to the isle of Avalon after his final battle, and that he would return to reclaim Britain for his people.

This aspect of the mythology had troubled King Henry II in the late twelfth century, before the monks of Glastonbury came up with an innovative solution to the problem.

A tomb was ‘discovered’ at Glastonbury in 1184 that was said to contain the skeletons of Arthur and his wife Gwenevere. This at once boosted the reputation of Glastonbury as a must-visit destination on the lucrative pilgrimage trail, while the confirmed news of Arthur’s death helped Henry in his propaganda wars with the Welsh.

It was no coincidence that in 1278 Edward chose to visit the site to reopen the tomb, confirm the presence of the skeletons, and arrange for their reburial in a lavish ceremony.

In case there should be any doubt about the mortality of Arthur, his skull and that of his wife were left outside the elaborate new tomb, clearly on display for any visitor to see.

Arthur and the conquest of Wales

The peace arranged after Edward’s 1277 campaign did not last, and when conflict resumed in 1282–3 the English forces would be engaged in a war of conquest.

When Llywelyn was killed, Edward took over his lands, where he would use mythology alongside law and military might to impose his will.

This was evident in the construction of Caernarfon Castle, built in imperial style on a site connected in Welsh mythology with Macsen Wledig. This character equated with the Roman emperor Magnus Maximus, who was symbolic of the inherited right to rule that passed from Rome to the Brythonic leaders.

An erroneous but widespread belief also named Macsen as the father of Constantine the Great, while Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed that Constantine was the grandfather of Arthur.

In the course of Edward’s 1283 campaign in Snowdonia, the king had ‘discovered’ the body of Macsen at Caernarfon, an act as fortuitous and well timed as that of the monks of Glastonbury who had ‘found’ Arthur and Gwenevere in the twelfth century.

Edward was back at Caernarfon in 1284, when he was presented with a key piece of paraphernalia associated with Llywelyn’s right to rule his principality – a gold coronet known as ‘Arthur’s crown’.

This was sent back to London, where it was presented to the king’s eldest son, Alfonso, at the shrine of Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey.

The royal court spent much of June, including the king’s 45th birthday, at Llyn Cwm Dulyn, a lake in the mountains of Snowdonia that was said to have mystical properties.

The use of the courts of the former princes was part of a deliberate attempt to emphasise both the humiliation and replacement of the old dynasty.

In July the court had moved to another such court, Nefyn on the Llŷn peninsula, the place where Gerald of Wales (d. 1223) claimed to have discovered a copy of the prophecies of Merlin.

Here, the royal party chose to further indulge their Arthurian fascination by holding a tournament that was referred to as a ‘Round Table’.

Determined to explore the extremities of his newly conquered domain, by early August Edward had reached the far tip of the Llŷn peninsula, taking in the tiny islands off the coast before returning to Caernarfon by 13 August, and to the English borderlands by 22 August.

At a parliament in London in May 1285, Edward led a procession of his magnates past the severed heads of Llywelyn and his brother Dafydd, carrying the princes’ most precious relic, the Croes Naid, said to be a piece of the true cross of Christ.

This was placed on the altar of Westminster Abbey, and later gifted to the nuns of St Helena at Bishopsgate, Helena being the mother of Constantine the Great, who claimed to have discovered the true cross.

Towards the end of the summer Edward staged another ‘Round Table’ tournament; held at Winchester Castle, this was a much grander affair than the event at Nefyn and may have been the occasion for the creation of the famous round table that hangs in the castle’s great hall today.

‘Arthur never held the fiefs so fully’

Wales was crushed, but the scale and intensity of Edward’s military activity would increase greatly later in his reign.

Wars in Scotland and France would dwarf the efforts and resources the king had expended in Wales, and it was in this period that the chronicler Pierre de Langtoft compared Edward favourably with Arthur, who so clearly fascinated the English king:

Ah God! How often Merlin said the truth

In his prophecies, if you read them…

Now are the islanders all joined together

And Albany [Scotland] united to the regalities

Of which king Edward is proclaimed lord.

Cornwall and Wales are in his power

And Ireland the great at his will.

There is neither king nor prince of all the countries

Except King Edward, who has thus united them

Arthur never held the fiefs so fully.

The king was deeply engaged with Arthurian mythology and made serious attempts to manipulate it. Yet his actions reflect the imposition of an English mythology, not an attempt to create a pan-British one. According to Professor Rees Davies:

The power which Edward I exercised in 1296 was not that of monarch of the whole of Britain, either in name or in substance, but rather that of the king of England who had brought the four countries of the British Isles more or less under his power.

The consequences of that fact, and of the way in which the power bloc had been assembled, cast their shadow over the history of the British Isles for generations, indeed centuries, to come. In a power bloc constructed from England, outwards, the status of the other countries and peoples of the British Isles was likely to be at best problematic, at worst inferior.

*You can read more about this subject in my book Edward I’s Conquest of Wales.

And remember that Dragon Tours can help you visit any of the Arthurian sites in Wales, Britain or Europe.